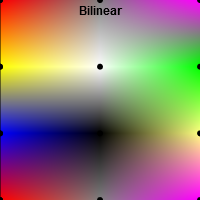

In the context of textures, bilinear interpolation is very important. Your task is to implement bilinear interpolation instead of nearest neighbor interpolation for the setup shown below. Colors are given at the black points; the nearest neighbor interpolation in the left square shows you which colors the points have.

Follow the instructions in the source code and implement the bilinear sampling method Basic1a.sampleBilinear.

Make use of the given helper functions.

Once you are done, the square in the middle should look like the square on the right.

This subtask is about MIP Mapping.

The first aim is to build the MIP map pyramid.

Follow the instructions in the constructor MipMap(texture1D, nLevelMax).

After implementation you should see the coarser two levels of the MIP map pyramid, which are currently black, depicted in color (beneath the surface).

Next, you should use the MIP map pyramid to set the colors of the pixels in the image plane.

Currently we always use the finest level of the pyramid.

You have to adapt the code in Basic1b.DetermineMipMapLevelOfPixel(i) accordingly.

The idea is to compute the footprint of a pixel in the texture.

If the footprint is larger than the texel size of a level, you should use a coarser level.

The footprint of a pixel can be computed by the distance of the top and bottom texture coordinate of the pixel (These coordinates are already computed, see comments in the source code!).

You can adjust the number of pixels on the image plane shown below:

This assignment will give you a look at perspective contortion and its consequences for rasterization. A triangle $\Delta ABC$ with $A = (0, 0, -1)^T$, $B = (0, 2, -3)^T$ and $C = (-2, -1, -3)^T$ is given. This triangle contains another triangle which consists of the centers of the edges $AB$, $BC$ and $CA$. Furthermore, a projection matrix $M$ is given which transforms $\Delta ABC$ such that $A'$ lies at the near plane and $B'$ and $C'$ lie on the far plane. $$ M=\left[ \begin{array}{rrrr} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -2 & -3 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \end{array} \right] $$

- Compute the transformed and dehomogenized vertices $A'$, $B'$ and $C'$. Make use of the given helper functions (see comments in the source file).

- Compute the centers of the edges $P_{A',B'}$, $P_{B',C'}$ and $P_{C',A'}$ from $A'$, $B'$ and $C'$. Is the drawn inner triangle perspectively correct? Which interpolation method do you know that would provide the same result?

- Compute the transformed and dehomogenized centers of the edges $P_{A,B}'$, $P_{B,C}'$ and $P_{C,A}'$ from $P_{A,B}$, $P_{B,C}$ and $P_{C,A}$. Is the drawn inner triangle perspectively correct?

Give answers to the theoretical questions in Basic2.txt!

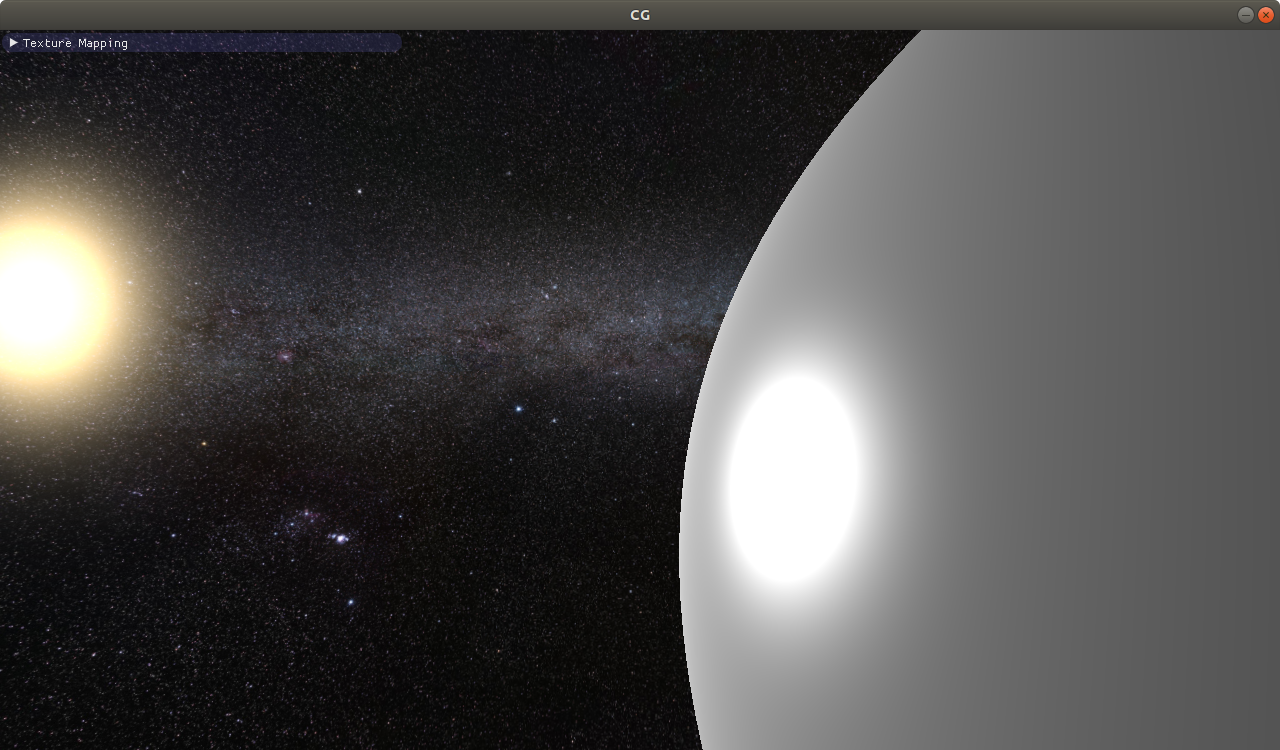

In this task, you should texture a plane, first with a texture containing colors, second with a texture

containing normals. Right now, you look at the plane (which is colored grey) from the top. You can change

the viewing angle using the W and S keys. There is a point light source hovering

over the plane, like in the Phong shading task of Basic Exercises 6.

On the right, you see a checkerboard texture. Several steps are needed to apply this texture to the plane.

- Set up the texture from the provided image.

-

In the vertex shader you can find an attribute for the texture coordinates. Define a varying

variable to pass them to the fragment shader. Assign the attribute to the varying variable.

Note that the WebGL warning "WebGL warning: vertexAttribPointer: -1 is not a valid index."

will disappear once you have done this. The warning appears because when

vTexCoordis unused, the shader compiler omits it and its location cannot be found. - In the fragment shader, define the same varying variable to receive the texture coordinates from the vertex shader. Define a uniform sampler holding the texture to be passed, and sample the texture at the texture coordinates.

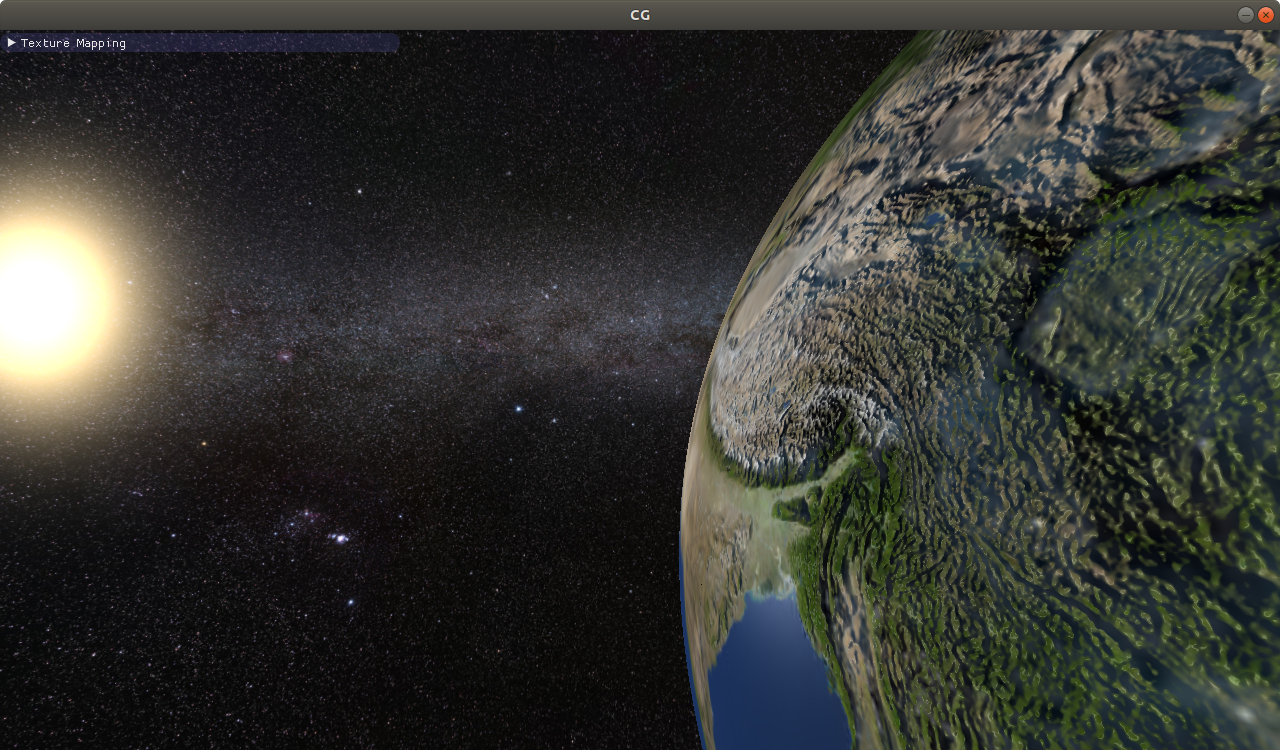

Once the texture is set up correctly, you see the texture in the upper left corner of the plane,

where the texture coordinates are smaller than $1$. To repeat the texture for texture coordinates greater than $1$ rather than clamping

it to the nearest value, you can check the associated checkbox. Have a look at onChangeRepeat()

to see how it works.

As soon as repeating is enabled, the texture covers the entire plane. When you change

the view angle, however, minification occurs in areas farther away, and ugly patterns arise.

To change this, enable MIP mapping by checking the associated checkbox. Have a look at onChangeMipmap()

to see how it works.

In next week's lecture, you will see what MIP mapping is and how it is used to prevent minification artifacts!

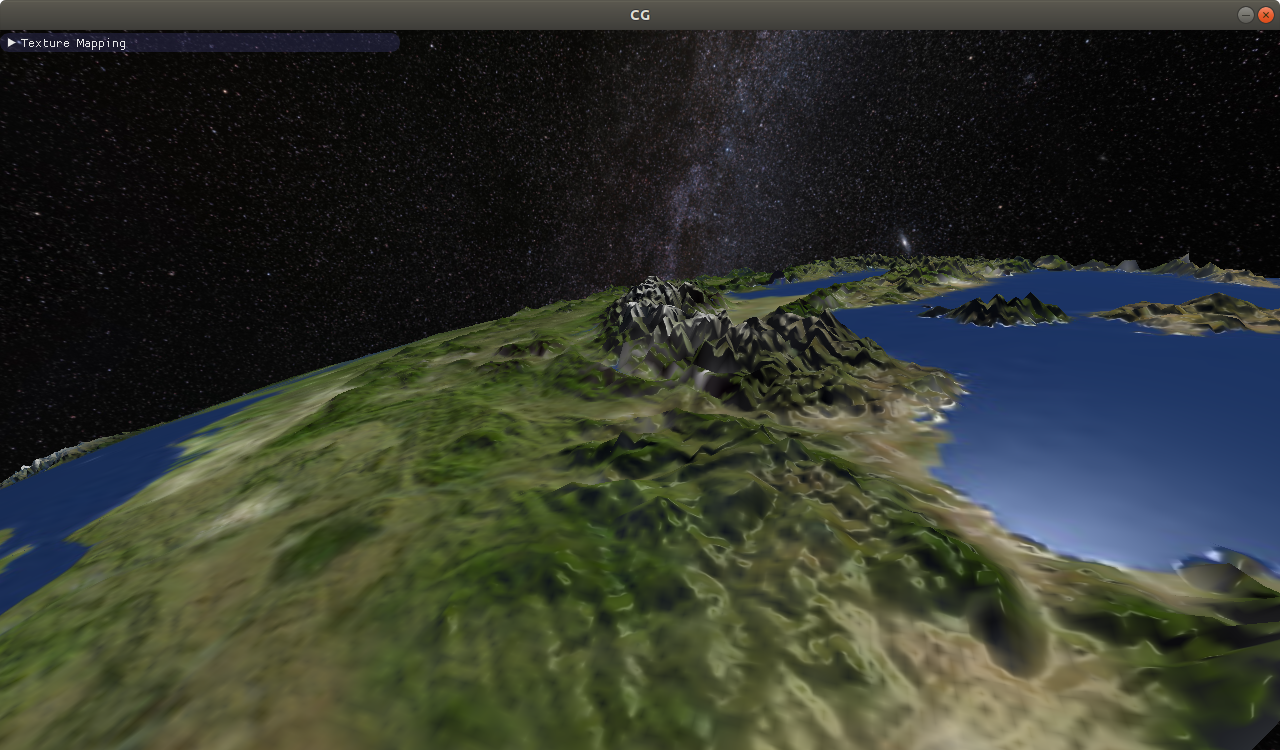

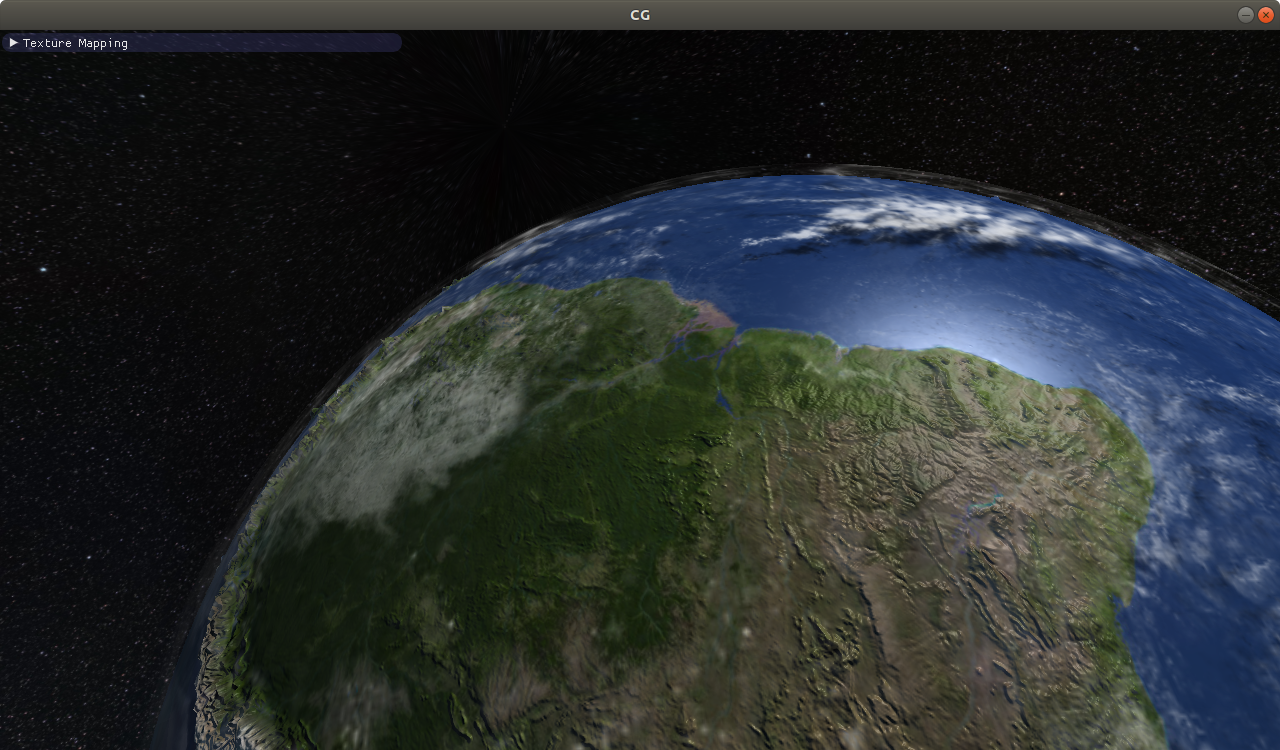

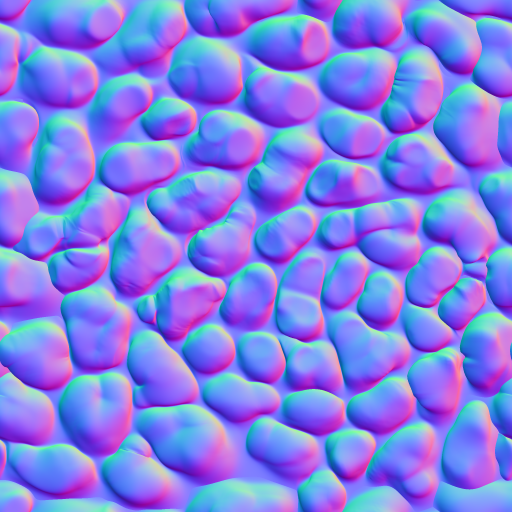

A texture can also be used to store additional information of a surface, such as normals. On the right,

you see a so-called normal map which stores normals encoded as RGB triplets. Once these normals are used

for lighting computation in the fragment shader, the plane does not look flat anymore, but as if covered with

cobblestone. Find the appropriate TODOs in the two submission files and apply the normal

map to the plane! You can reuse the texture coordinates already used in the first subtask.

Be aware of two things: First, the normals are stored as colors, which means that their values have

been mapped to $[0,1]$. You have to bring them back to $[-1,1]$ to use the normals. Second, unlike in the last

subtask, the plane should be covered with one single, unrepeated instance of the texture. Therefore, you have

to change the texture coordinates to be in range $[0,1]$ rather than $[0,width]$ and $[0,height]$, respectively

($width$ and $height$ are given in the uniform planeSize!).